From: Kenneth

A, Schechter (Forwarded to SpadGuy by Bill Montague)

Sent: Tuesday, January 23, 2001 5:33 PM

Subject: Blind and Alone Over North Korea

Last Wednesday I received a phone call from the publishers of a series of books called Chicken Soup for the Soul. It was explained to me that these were inspirational stories, each one in a particular area of interest. They are putting together a new book called Chicken Soup for the Soul for Veterans.

In the course of their collecting suitable stories, apparently several people recommended the story of my blind flight during the Korean War. Many of these were from people in the crew of my ship, the USS Valley Forge. The Valley Forge heard and recorded the radio transmissions between me and Howard Thayer and played them back for the whole crew the same night.

The editor wants to include my story. I recommended the Saturday Evening Post article of November 29th, 1952. That article, written by an officer on the Valley Forge, is the most accurate account I have seen. For example, the radio transmissions quoted came from the recording made during the incident and from interviewing Howard and me at the time. The editors' problem with this is that this article is a third person description. They want it to be a first person narrative, from my point of view.

Accordingly, I have written up the adventure from my perspective. I just sent it along to the "Chicken Soup" people and am told it needs editing and shortening by some 300-400 words to conform to their format. It will appear in the edited form in the book.

You have all seen the Saturday Evening Post article (from which I took the quotes of the radio transmissions) and I thought you might like to see this. The version in the book will probably be better but this one is ready now and I thought I'd send it off to you while it is on my mind.

XXXOOO, Ken

I was blind, stunned, in pain, bleeding profusely and very much alone. At the controls of my Navy Skyraider attack plane over Wongsang-ni, North Korea, I was climbing, inexorably, toward a solid overcast at 10,000 feet -- from which there could be no return.

March 22, 1952. I was just 22 years old. Dawn found me on the flight deck of the USS Valley Forge in the Sea of Japan, warming up my Skyraider. As a pilot in Fighter Squadron 194, the "Yellow Devils," I was the standby in case one of the 8 planes scheduled for the morning's flight became inoperative. Such happened. Charlie Brown's plane lost its hydraulic system and I was launched in his place. This would be my 27th mission bombing North Korea. Today's targets were enemy marshalling yards, railroad tracks and other transportation infrastructure.

On the 9th of my planned 15 bomb runs, at 1200 feet, an enemy anti-aircraft shell exploded in the cockpit. Instinctively, I pulled back on the stick to gain altitude. Then I passed out. When I came to, sometime later, I couldn't see a thing. I was blind.

There was stinging agony in my face and throbbing in my head. I felt for my upper lip. It was almost severed from the rest of my face.

I called out over the radio through my lip mike (which miraculously still worked), "I'm blind! For God's sake, help me! I'm blind."

Lieutenant (jg) Howard Thayer heard the distress call. He saw my Skyraider, still climbing, heading straight towards a heavy overcast at 10,000 feet. If I entered those clouds there would be no hope whatsoever.

He called out, "Plane in trouble, rock your wings. Plane in trouble, rock your wings."

I did so.

Then came the order, "Put your nose down! Put your nose down! Push over. I'm coming up."

I did so.

He climbed and flew alongside my plane and radioed, "This is Thayer this is Thayer! Put your nose down quick! Get it over!"

I complied. Howie Thayer was my roommate on the Valley Forge. Hearing his name and his voice gave me just the psychological boost I needed.

He continued, "You're doing all right. Pull back a little. We can level off now."

According to Thayer's description, the canopy was blown away. My face was a bleeding mess. The areas around the cockpit were a crimson that turned dark and blended with the Navy Blue of the Skyraider as the blood dried in the slipstream. He wondered how I was still alive.

I began to think clearly, in my moments of consciousness and began to try to help myself. I pulled the canopy release to get some air. It didn't work. Then I realized the canopy had been blown away. The last thing I needed was more air. The 200 mile per hour slipstream and unmuffled engine noise made sending and receiving the radio transmissions difficult.

I somehow poured water from my canteen over my face. For a fleeting instant there was a sight of the instrument panel, which disappeared immediately. I was blind.

I radioed, "Get me down, Howie. Get me down"

Per his next transmission, I dropped the rest of my bombs.

Howard kept up a stream of conversation, "We're headed south, Ken. We're heading for Wonsan (a port and prime target on the Sea of Japan). Not too long."

By now my head was throbbing and the blood running down my throat made me want to vomit. I hurt. I was unable to get the morphine from my first aid kit.

"Get me down, Howie!"

"Roger. We're approaching Wonsan now. Get ready to bail out."

To which I replied, "Negative! Negative! Not going to bail out. Get me down."

On my second mission, my wingman's plane was disabled by enemy flak and he was forced to ditch it into the frigid ocean off Wonsan. By the time his plane finished skipping across the water and stopped it was a sheet of ice. He got out of the cockpit and waved. I circled him and radioed for help before returning to the Valley Forge when it looked like everything was okay. Nothing could have been further from the truth.

Due to the numbing cold we wore rubber immersion suits. His was of the first version we were issued. They were unsatisfactory. Only one of the two carbon dioxide cartridges that inflated his life vest worked. He was somehow unable to inflate and get into the rubber life raft he carried. A rescue helicopter, some 5 miles away on Yo-Do Island at the mouth of Wonsan harbor, was inoperative. The two destroyers that usually were shelling near Wonsan were 50 miles north.

Tom Pugh's remains were pulled from the Sea of Japan some 90 minutes after he landed. His immersion suit was half full of water.

I would not bail out. I knew that Howie could get me back behind the front lines into friendly territory or I would die in the attempt. He understood my decision. We turned and headed south.

30 miles behind the front lines, on the coast,

was a Marine airfield designated

K-50. This was our destination. Whether I could make it that far

was a moot point. I kept drifting in and out of consciousness.

Howard spotted a cruiser shelling enemy positions and knew that this was the bomb line. South of the bomb line was friendly territory.

The conversation continued, "We're at the bomb line, Ken. We'll head for K-50. Hold on, Ken. Can you hear me, Ken? Will head for K-50. Over."

"Roger."

"Can you make it, Ken?"

"Get me down, you miserable bastard, or you'll have to inventory my gear!"

(In case of an aviator's death, a shipmate must inventory his personal belongings before they are shipped home not a welcome chore. Howard and I had designated each other for this function.)

I continued to follow Thayer's directions but my head kept flopping down from time to time. He felt that I probably couldn't have made it to K-50. He was probably right. He decided to get me down right away.

Immediately behind the front lines was a 2000 foot deserted dirt airstrip named "Jersey Bounce" that the Army used from time to time for its light planes that did artillery spotting. Thayer decided to have me land there.

"Ken, we're going down. Push your nose over, drop your right wing. We're approaching 'Jersey Bounce.' Will make a 270 degree turn and set you down"

"Roger, Howie, let's go."

"Left wing down slowly, nose over easy. A little more. Put your landing gear down."

"To hell with that!" was my instantaneous reply. I had seen this field on earlier missions and could picture it in my mind's eye. In such an emergency situation and on such a primitive and short field, it was very much safer to land on my belly.

"Roger, gear up," Thayer concurred.

Upcoming was the most critical part of the flight. One slip would spell disaster.

From his plane, flying 25-50 feet away from mine and duplicating my maneuvers, Howard's voice was cool and confident, "We're heading straight. Flaps down. Hundred yards to the runway. You're 50 feet off the ground. Pull back a little. Easy. Easy. That's good. You're level. You're O.K. You're O.K. Thirty feet off the ground. You're O.K. You're over the runway. Twenty feet. Kill it a little. You're setting down. O.K. O.K. O.K. Cut!"

The shock wasn't nearly as bad as I expected. Some 45 minutes after the shell blew up in my cockpit, the plane hit, lurched momentarily and skidded to a stop in one piece. A perfect landing. No fire. No pain, no strain. The best landing I ever made.

Thayer, elatedly, "You're on the ground, Ken."

(I should mention that most of our transmissions were picked up and recorded on the USS Valley Forge and played back for the crew that night.)

After cutting the switches I clumsily climbed out of the cockpit. Almost immediately an Army Jeep with 2 men came, picked me up, and took me to a shack on the edge of the field. A helicopter picked me up and flew me to the Marine airfield, K-50, where doctors at their field hospital started to patch me up and give me pain killers. They felt I needed much more medical expertise, so a transport plane flew me to Pusan at the tip of South Korea where I was taken aboard the Navy Hospital Ship, USS Consolation. There was immediate surgery. The bandages on my eyes were not removed for several days. I was eventually returned to the United States, to the Navy Hospital in San Diego, from which I was retired due to medical disabilities on August 31, 1952.

Sight was restored to my left eye, but I am still blind in my right eye. My career as a Navy Carrier Pilot was over. My life was not. I am still living on borrowed time and am grateful for each and every day.

Afterward

College Life

I became a Navy Pilot under a program whereby the Navy sent

me to UCLA for two years, then to flight training. (I might mention

that 2 of my better known classmates were Neil Armstrong and Joe

Akagi, the first Japanese-American naval aviator.)

I wanted to finish up my college training and started as a junior

at Stanford in September, 1952. I was disappointed with the general

lack of support for our Armed Forces in Korea by the civilian

population. In the fall, a blood drive on campus netted 176 pints.

I became Chairman of the next blood drive in the spring of 1953.

The response by the Stanford Community was fabulous. We collected

4640 pints of blood in a 5-day drive which, I am told by the Red

Cross, is the record for a continuous blood drive.

Howard Thayer Howie made the Navy his career. In January, 1961, while flying a night mission in an A-4 attack plane from a carrier in the Mediterranean Sea, both he and his squadron commander flew into the water while on landing approach. Their remains were never recovered. Howie was survived by his wife and 3 small children.

The Trusty Skyraider

The plane that I landed at "Jersey Bounce" was

jacked up, a new propeller installed, and was flown back to the

Valley Forge for repairs. It was returned to service.

I'm Jon Ewing and I was flying that airplane as Sandy 2 on 20 Dec,1968. I remember thinking I was going to miss the Bob Hope Show and Ann Margaret, which was 22 Dec. I did make the show, in fact I was invited back stage to interview with Bob Hope. I have a slide of me with one of the "Gold Diggers" sitting on my lap. Her name was Sandy.

We were trying to rescue a Navy A-6 crew that had been shot down the night before. Ray Shrum was Sandy 1, Jack Watts was three, and I think Ron Furtak was four. Ray was trying to locate the RIO visually, but he was in a fog bank by a major road. This was in southern Laos. As Ray flew low over the survivor I would watch for ground fire. I saw a quad ZPU site open up on him and rolled in to mark it. My WP rocket went into the fog bank and Ray couldn't spot it. He made two more passes while I rolled in with guns, rockets, and CBU-25 on the pull off.

On the third pulloff a 37mm nailed me in the left gearwell. The canopy was blown ajar and the cockpit filled with smoke. I pulled the five red handles and then blew the canopy off. I saw the fire in the left wing and started heading for the nearest karst. I then realized the engine was still running. Nobody would answer my calls so I figured the radios were out. I then looked back and saw the FM antenna blown to pieces, switched to VHF and saw Jack joining up. The fuel guage read zero and the fire was still burning, but the engine was running and I got the fire out by slipping the aircraft away from it. The Mekong was my next objective and then Ubon. I tried the gear, but we alredy knew that it wasn't going to work so I landed gear-up using the tail hook on the approach end barrier. I was awarded the Silver Star for the mission and the invincible Skyraider was class 26.

copyright by George J. Marrett.

Excerpted from the book: "TEST PILOT: Death in the Sky"

During my combat tour in Southeast Asia (SEA), I served with the 602nd. Fighter Squadron (Commando) from April 1968-1969 flying the Douglas A-1 Skyraider on Sandy rescue missions and Firefly strike/forward air controller (FAC) missions out of Udorn and Nakhon Phanom (NKP) Royal Thai AFBs, Thailand.

The war seemed to me to be going no where. Our Skyraiders would destroy and silence a few gun positions one day only to have one of our aircraft get shot down in the same area a few days later. It was a war without purpose and direction.

Battle damage?

About halfway through my year assignment, I was scheduled to lead a morning two-ship Firefly strike mission over the central part of the Plaine-de-Jars (PDJ) in Northern Laos. Just as I released ordnance over the target in a steep dive bombing pass and started my pull-up, the engine began to run rough. Leveling off, I attempted to add power but the engine back-fired badly. My best guess at the time indicated I had probably taken a hit in the engine from ground fire. The cylinder head temperature went to full hot. I knew I was at least 100 miles from home base at NKP. With only partial-power available, I could not maintain level flight. The aircraft was slowly dropping. I couldn't make it home.

Approximately 20 miles west of my position was Lima Site 21 located on the southwest corner of the PDJ. Lima Site 21 had an east-west narrow dirt landing strip used by the CIA and Laotian military. It was surrounded by enemy territory. I headed west.

Forced Landing...

Recently one of my squadron mates, Jack Watts, had experienced an engine failure and attempted an emergency landing on the dirt strip at Lima Site 21. It was late in the afternoon and the sun was just above the horizon. Jack had never landed on the strip before and set up a dead-stick landing pattern so as to land heading to the west. Engine oil was leaking over the front windscreen, causing him to have great difficulty seeing the landing field. On final approach the sun was directly in his face and only because of his expert skill in handling the Skyraider was he able to successfully land the aircraft on the very end of the strip. Unfortunately, the strip had a big hump in the middle. With the sun in his eyes and the engine oil blocking his view, Jack thought he was going to run off the end of the strip. If he went off, the Skyraider would probably nose over and he could be trapped in the cockpit. No fire or rescue units were stationed at Lima Site 21, you would have to take care of yourself. Fearing this danger, he retracted the landing gear and the aircraft skidded to a stop with dust flying behind him. After the aircraft came to a stop, he opened the canopy and stood up on his seat. To his great surprise, when the dust cleared he found out that about half of the strip was still in front of him!

Having heard the details of Jack's close call, I looked over the scene. I had the advantage of the sun over my left shoulder and a clear windscreen. My wingman had contacted the Lockheed C-130 airborne command and control ship called Crown, reported my airborne emergency and asked them to start a rescue effort. He joined up in formation on my wing and helped me set up a partial-power dead stick landing pattern.

As I touched down on the end of the dirt strip, the field did indeed look short and narrow, but I applied brakes and easily slowed down. I looked for a place to park the Skyraider. I found a flat spot off to the side, taxied over and shut down the engine. My wingman radioed he was heading back home to NKP and I saw him fly away. As I stood up in the cockpit, took off my helmet and watched him fly off to the southeast, I thought to myself, "this is going to be a long day."

Safe on the ground, surrounded by enemy territory...

Within a few moments, a jeep drove up to the side of my aircraft and parked. A white-skinned grizzled looking male in his late 50's dressed in dirty rumpled clothes got out of the jeep. I was quite apprehensive knowing I was in territory surrounded by the enemy and own my own. The man spoke English, indicating he was with the CIA. Even though it was only late morning, he appeared to be intoxicated and a little incoherent. My first thought was that living in a remote area like this, behind enemy lines, it might be smart to get paid every day. You wouldn't know if you would live through the day. Maybe he converted his pay to alcohol everyday or in fact was paid in drink. Anyway, he asked me if I wanted to view the field. I was reluctant to leave the Skyraider, but on the other hand felt I might be safer away from the plane, and certainly the Jolly Green rescue helicopter wouldn't be able to pick me up for at least 10-15 minutes, if then. As we drove around the dirt strip, I saw aircraft that had crashed and been pushed off to the side. Laotian men and women were walking around some distance away -- not in any type of military uniform that I could recognize. On the other hand, I would easily be identified as an American pilot by my flying suit. How would I recognize the enemy? My jeep driver's clothing began to take on a more favorable appearance.

Jollys to the rescue...

Soon I heard that wonderful sound of helicopter blades spinning in the air, "wop-wop-wop." A Sikorsky HH-3 using the call sign Jolly Green landed on the dirt strip. I gathered my helmet, maps, strike photos, checklist, survival vest, gas mask and jumped aboard. We were airborne and headed south to the nearest base: Udorn Royal Thai AFB, Thailand. I lay down on a bunk bed in the back of the chopper, put on my flight helmet and plugged into the intercom. The chopper pilots wanted to know what had happened and I explained my engine problem. They contacted Crown and reported that the Skyraider pilot was safely aboard with no injuries. Finally I began to relax. The day might actually be short and maybe even enjoyable. I saw myself at the Udorn Officer's Club having a late lunch, stopping in at the Base Exchange (BX) for a little shopping, then catching a flight home on the Lockheed C-130 Hercules which circled all the Thailand bases, dropping off mail and supplies. No sweat. Another combat mission in the book. One more day closer to going home. "Only 159 days left, but who's counting?" was the phrase in vogue at the time. We ALL counted the days remaining to rotation back to the good old USA.

Not so fast...

As the chopper crossed the Mekong River, separating Laos from Thailand, the command post called the Jolly Green crew on the UHF radio. The Wing Headquarters at NKP had scheduled a Fairchild C-123 Provider cargo aircraft to fly a group of Skyraider mechanics and tools to Lima Site 21 in an attempt to repair my broken aircraft. If the Skyraider couldn't be repaired by sunset, the crew would be prepared to blow up the plane preventing it from falling into the hands of the enemy. It would take several hours to round up the resources, so they didn't know when the plane would actually arrive. But the command post ordered the Jolly Green to reverse course and fly back to Lima Site 21. Headquarters said a pilot would be needed to fly the Skyraider back to Thailand if it could be repaired. I was the pilot.

The Jolly Green helicopter landed back at Lima Site 21. I assumed the crew would shut down their engines and stand rescue alert there. The crew informed me that it was too dangerous to leave the chopper on the ground and they needed to be airborne in case another rescue were required. They took off heading southeast like my wingman had done several hours before. This was going to be a long day after all!

In what seemed forever, I waited for the C-123 to arrive. The sun had moved west across the sky and I was still far from my home base. I got out my .38 caliber revolver and rechecked the six shells in the chamber. Sitting under the wing of my aircraft I wondered if the CIA type might have been a Skyraider pilot who had also made an emergency landing there some time ago and never got back home!

The C-123 finally arrived with five mechanics and all kinds of tools. The repair was actually quite simple. Evidently, a couple of magneto leads had come loose in the ignition system. Shortly, I started the engine and it sounded as sweet as I had ever heard from one of the huge Pratt & Whitneys. Just as the sun set, I was airborne. It was going to be easy to find my way home, just head the same direction as my wingman and the Jolly Green had taken many, many hours before.

Gear in the well...

That evening back at NKP, I was informed that my Jolly Green rescue crew expected me at the Officers Club for the standard rescue party. It was the custom for every aircrew rescued by the Jolly Green and Sandy force to buy a round of drinks for all involved in their rescue. The survivor was also lifted in the air by the rescue crew and thrown over the bar. A three foot Jolly Green Giant cloth doll stood on the counter behind the bar. It held in its hands an eight inch square white plastic board in which a number written in black grease pencil indicated the total number of aircrew rescued by the Jolly Greens. The survivor would erase the old number, and print the new to the applause and celebration of all in attendance.

How George really got his Purple Heart...

My Jolly Green rescue crew had been at the bar for a long time. They sounded as incoherent as the CIA type I had spent time with at Lima Site 21. I bought a round of drinks for them and told them, as Paul Harvey would say, "the rest of the story." We finished several rounds and they were ready to throw me over the bar. But I wasn't planning to go over the bar. It was my opinion that the Jolly Greens should not get credit for a rescue since I was returned to the exact same place in which I was rescued. They explained that they had picked me up in enemy country and transported me back over the Mekong River to friendly country. That was all that was required for an official rescue. It wasn't their fault that the command post ordered them to return me to Laos. To make my point, I said if we were playing baseball they would be lucky to get an assist, it was definitely not a put out.

Nevertheless, I was lifted in the air. Unlike the previous survivors who gladly went along with this tradition, I resisted. We struggled for some time. I was finally thrown over the bar, but two of the Jolly Greens held tightly in my arms crashed over the bar with me. In the process I struck my forehead on the corner of the wooden bar ending up with a deep gash that started to bleed. It was unlike any rescue celebration ever conducted at NKP at that time. Maybe ever.

The injury to my forehead left a scar that

remains to this day. Years later my two young sons asked me about

the scar. I said I got it in the war! I never explained to them

what actually happened to me. It was the kind of war you couldn't

explain to anyone.

On October 19, 1965 a flight of 4 A-lEs from the 1st Air Commando Squadron, then stationed at Bien Hoa AB, RVN were scheduled for a combat mission in South Vietnam. Just before takeoff the flight leader, Captain Melvin Elliott, was told they were being diverted to Plei-Me Special Forces camp, approximately 30 NM south of Pleiku. The flight departed and flew to Plei-Me uneventfully. Upon arriving just before dawn there was a flight of F-l00s in the area working with a C-123 with a FAC on board. When the F100s had expended their ordnance the A-lE's were directed into the area. The flight leader was told that the compound was in trouble from an attack by what was later determined to be regular North Vietnam troops. (The first confirmed in South Vietnam.)

The A-l flight was operating on an FM radio frequency and had the flare ship as well as the American Commander of the compound on the same frequency. During the attack the compound Commander directed the A-l's to drop the napalm that he knew they had on-board right on the perimeter of the camp. At times the pilots of the flight noticed that the igniters from the napalm cans were going over the wall into the trenches inside the compound. After all ordnance had been expended the flight returned to Bien Hoa without incident. Upon landing three of the four planes had several bullet holes (small caliber) in them.

Back to Plei-Me...

Two days later, 21 October 1965 (Sunday), I was in the officer's club having a drink with a friend from Hurlburt who was flying the AC-47, (PUFF), aircraft. This pilot asked me what medals I had been awarded during our tour there and I replied, "The only ones left are ones that hurt or scare you." Then the phone in the club rang and it was the command post asking for A-lE pilots to go on alert. The pilots on alert had just taken off on their third mission of the day which was the point at which they would have to be replaced. I answered the phone and told the duty officer I would round up four new pilots and would report to the command post ASAP. The four new pilots, including myself, arrived at the command post, were briefed and assigned aircraft, picked up our flight gear and proceeded to the aircraft to "cock" them for alert. We had just loaded our gear in the planes when the command post called and ordered two planes to launch. My wingman and I were to be the second two to launch so we proceeded to the alert trailer to get any rest possible. About 2 hours later the phone rang ordering the second two planes to proceed to Plei-Me and rendezvous with a flare ship and an Army Caribou at 12:30 am. The flight to Plei-Me was uneventful and rendezvous was effected with the flare ship. The weather in the area at the time was about 1000 foot ceiling with good visibility under the clouds. The flight set up an orbit around Plei-Me awaiting the Caribou. The flare ship was keeping the area lit from above the clouds.

I'm hit...

After about an hour in the area I advised the flare ship that we would be able to stay in the area longer if we expended the external ordnance we were carrying, napalm, CBU and rockets. The compound marked an area with a mortar round and we expended our external ordnance. Upon completing this, the flight again set up an orbit awaiting the arrival of the Caribou to resupply the compound. At approximately 2:15 am, I requested the status of the Caribou and was told that it had been canceled for that night. I informed the flare ship and compound that we would have to leave the area shortly but that we could strafe any likely areas with our 20mm cannon before leaving. The compound again marked an area with a mortar round and I rolled in on a strafing pass. As I pulled off the target I noticed that things were quite bright. I looked at the left wing and it was ablaze. At this time I called my wingman and notified him that I was on fire. The wingman requested that I turn on my lights so he could see me. My thoughts, at that point were that, if he couldn't see me with the fire that was burning he for sure wouldn't see the lights of the aircraft. At that point, I planned to maneuver over the compound and bail out (no Yankee extraction system at this time). Before getting into position over the compound the flares went out and it was impossible to see the ground. I continued in the orbit, at approximately 800 feet altitude awaiting the illumination of flares so I could see the ground. Before this happened the controls of the aircraft failed and I notified all concerned that I was bailing out at that point.

Over the side...

As I was attempting to bail out of the aircraft I became stuck against the rear part of the left canopy. My helmet was blown off immediately when I stuck my head out of the cockpit. A few days before this mission I had cut the chin strap off the helmet as the snap on it had become corroded and would not unfasten after a mission. At this point the aircraft was out of control and was rolling due to the fire burning through the left wing. After freeing myself from the aircraft, I reached for the D-Ring which was not in the retainer pocket on the parachute harness. However, I found the cable and followed it to the ring and pulled it. The chute opened and shortly after flares lit and I could see that I was going to land in the trees in the area. After landing in the trees, approximately 50 feet above the ground I bounced up and down to insure that the chute was not going to come loose and then swung over to the trunk of the tree and grasped a vine nearby. I had lost my hunting knife during the bailout so I was forced to abandon the survival kit that was a part of the parachute.

After climbing down the vine to the ground, I sat down and thought about the situation for a short time and assessed what equipment I had. I had a 38 cal revolver with 5 rounds of ammo, a pen-gun-flare, a strobe light, a two way radio, which at times was a luxury to A-1 pilots, my Mae West and a brand new "chit book" from the Bien Hoa Officers Club.

After regrouping on the ground I got out my two way radio and contacted my wingman who was orbiting the area. I told my wingman, Robert Haines, that I had him in sight and advised him when he was directly overhead and then instructed him to fly from my position to the compound and that I intended to attempt to make it to the compound. About 30 minutes later Haines had to leave the area and proceed to Pleiku as he was running short on fuel.

A failed rescue attempt...

I proceeded toward the compound and when I felt I was getting close to the perimeter a severe fire-fight broke out. At this point I found a likely place to hide out and stayed there the rest of the night. Shortly after dawn I spotted an O-1 aircraft orbiting the area and turned on my radio and called him several times before getting an answer. I had forgotten my call sign and used my name, when calling the bird-dog. By identifying different landmarks the bird-dog (which turned out to be an Army A/C) pinpointed my position. I stayed fast all day and just after dusk the bird-dog (same pilot) told me that a Huey was coming to get me out. Shortly afterward, radio contact was made and I was told to get into the best position I could to get picked up. The Huey arrived on the scene and I moved from my hiding place onto a small trail through the brush. When the Huey came around with lights out I turned on my strobe. The Huey made two orbits and on the third circle came in and turned on his floodlight. At that point a 50 cal machine gun opened fire about 50 yards from my position. The Huey turned his lights off and left the area. I put the strobe in my pocket and got off the trail into the brush and laid as low as possible. About 10 minutes later two people (North Vietnamese soldiers), came down the trail with a flashlight. At this point I was about 20 feet off the trail and flat on the ground. The two fellows were chatting as if they were out for a Sunday stroll and shining their flashlight from one side of the trail to the other. On one of the sweeps of the light it came to within about 2 feet of me and then the next sweep was beyond me. After the two fellows were satisfied that I was not in the area, I found a new hiding place and settled down for the rest of the night. At this time it was about 8 pm. There was no sleep for me as aircraft were in the area the entire time I was on the ground. Between them and the mortars it was quite noisy. One thing I learned during my tour at "Plei-Me" was that a bomb must get quite close to an individual flat on the ground to cause him any great grief.

As dawn, (my second on the

ground), approached, I heard the familiar sound of a C-47 in the

area. I got out of my hiding place and saw an AC-47 orbiting with

the business side toward me. The aircraft made a couple of orbits

as I was going around the trunk of a large tree similar to a squirrel

who is being hunted. Shortly afterward, the AC-47 opened fire

with his guns, fired a short burst and departed. I later learned

that they had experienced an engine problem and returned to base.

As dawn, (my second on the

ground), approached, I heard the familiar sound of a C-47 in the

area. I got out of my hiding place and saw an AC-47 orbiting with

the business side toward me. The aircraft made a couple of orbits

as I was going around the trunk of a large tree similar to a squirrel

who is being hunted. Shortly afterward, the AC-47 opened fire

with his guns, fired a short burst and departed. I later learned

that they had experienced an engine problem and returned to base.

After two nights in the jungle...

Around 8 am I contacted a Bird dog in the area and through identifying landmarks, he again pin-pointed my position. The FAC (USAF) said he was going to throw smoke grenades to get a better position on me. Then, I didn't really think that was a good idea but the FAC threw all the smoke he had but never got any close enough for me to see. He advised he was going for more smoke and left the area. At this time another Bird dog arrived and advised me that a chopper was coming to pick me up and to get into a suitable area. I moved into an opening clear of brush but full of grass 5-6 feet high, and rather swampy underneath. Upon reaching the middle of this clearing I contacted the FAC and was advised that the chopper had been diverted on a "HIGHER PRIORITY" mission. This was really the only time while I was on the ground that I was completely demoralized. I proceeded back to the place I had hidden out all night and then decided that I was going to move away from the compound to make it easier to get picked up. During the move, about 1/2-3/4 mile I came across a small stream and washed my face up somewhat and washed my mouth out. This made me feel somewhat better.

I came upon a rise in the terrain and after the climb I came upon a fair sized clearing. I spotted a clump of bamboo and started for it to hide out, when an object darted out of it. After my heart started again I saw that it was a wild pig. I proceeded into the bamboo thicket and contacted a bird dog orbiting overhead. I again pin pointed my position with the bird dog, who said he was going to go for some food and water, as they did not know how long it would be before I would be picked up. After he left I realized that the only thing I had that I could open a can with was my pistol and five rounds of ammo.

Picked up at last...

After 30 minutes I again contacted the Bird dog and he said to come on the air again in 15 minutes. At the time I turned my radio on again I heard several pilots talking on "GUARD," several of whom I recognized as A-l pilots. The FAC said that an H-43 AF rescue chopper was about 5 minutes out and that the A-ls would be dropping napalm along a tree line about 100 yards from my position. He advised me to move into the middle of the clearing as soon as the A-1s passed over. Doing this, I spotted the H-43 coming in about 20 feet off the ground directly toward me. The pilot got into position and was forced to hover because of the brush in the grass. This created a huge wave of grass that I was forced to crawl through. Upon getting to the chopper I was dragging many vines that grew in the grass. The PJ on the chopper was hanging out the door and I stepped on to,(I thought the skid but instead got on the wheel). As soon as I reached up the PJ told the pilot he had me and away we went. The wheel rotated and I was hanging by my arm and the PJ's arm. I looked up at him and said I was not going back down there alone as he pulled me into the chopper. This was about noon and a total of approximately 36 hours on the ground.

After arriving at Pleiku there was some scrounging around trying to find a way for me to get back to Bien Hoa. Ultimately an A-l driven by Gail Kirkpatrick was diverted into Pleiku to pick me up.

After arriving at Bien Hoa an intelligence Sgt from Saigon was there to debrief me and the most redundant question was, "Capt Elliott were you scared at any time?" After debriefing and being checked over by the Doc I asked if my wife in Phoenix had been notified of this episode and could not get a definite answer. I then asked the Wing CO if I could call back on the Hot Line to talk to her. At this time it was 5 am in Phoenix. I got through to the operator at Luke AFB and gave her my number. She advised me she could not ring off base numbers. I kept her on the line and told her why I was calling and she put the call through. My wife had not heard of any of the events about my bailout and ultimate rescue, so I briefly told her, and when she hung up, she got the local newspaper which had my picture on the front page, along with the story.

There is no way of saying thanks to all the people involved in a successful rescue mission and there is no way to tell someone who has not been through such an ordeal what it is really like.

"Thanks to all involved"

Mel Elliott

Webmaster's note: These newspaper stories appeared shortly after Mel's remarkable ordeal.

The year was 1970, the place was northeast Thailand on a typical dark Southeast Asia night. I was number 2 in a flight of two A-1 Skyraiders about to depart on a night interdiction mission. Major Pete Lee was the leader and as he began his takeoff roll, I watched the blue flame from the exhaust stacks of the big R-3350 disappear into the night. The only thing that remained visible was the red rotating beacon high on the A-1's tail. Thirty seconds later it was my turn, I added power bringing the manifold pressure to 56 inches and watched the tachometer settle down at 2800 rpm. I'll never forget the throaty roar of 2700 horses turning a thirteen and half foot four-bladed propeller. Lots of right rudder to counter the left turning force of torque, I raised the tail at 50 knots (the A-1 had a conventional gear) and accelerated down the runway. Approaching 110 knots I rotated allowing the 25,000 lb. airplane to begin to fly. "GEAR UP" after airborne and plunge into the darkness.

Outside the airbase perimeter there were virtually no lights so as you climbed away from the runway, it was like flying inside an ink bottle. Ahead and above I could see Pete's red rotating beacon. Airborne now, I set the climb attitude on the antiquated attitude indicator (the A-1 was a 1950's airplane in a 1970's war). I reduced the MAP to 46 inches and brought the prop back to 2600 RPM for a normal 46-26 climb. Normally one would start the flaps up now but my personal technique was to close the cowl flaps first before raising the flaps. This allowed me to climb a little higher at takeoff flaps before cleaning up and accelerating to a normal 140 knot climb. The cowl flaps were electric so one held the switch to "CLOSE" for a count of four. After closing the cowl flaps, I raised the flaps and scanned the instrument panel. "What's going on here?" The engine sounds right, the attitude for climb is right, the airspeed is a little low, but the altimeter reads "field elevation" and the vertical velocity indicator (VVI) is "zero"!! About now before I can get excited, the VVI indicates maximum climb rate and the altimeter spins to about 800 ft above field elevation and stops. The VVI returns to 0 and the altimeter remains at 800 ft. I take a quick peek over my shoulder to see if the airport seems to be in the right place and that I am in fact climbing. It is, and Pete remains about the same place in my windscreen ahead and above me. Rechecking the attitude, the airplane feels like it should feel climbing at 140 knots. After a short time, the VVI needle again indicates maximum climb and the altimeter spins up another 800 ft. I now suspect a pitot / static system problem. The airplane had been washed earlier in the day and I wonder if water had got into the static system plumbing. I don't have the luxury of selecting an alternate static air source as we can in most Cessna single engine airplanes and other light airplanes. So I watch the altimeter hiccup its way to 10,000 ft. as I advise Pete of my predicament. I reduce the power to a cruise setting for this weight having climbed an estimated 1000 ft above Pete's altitude and again everything appears OK.

Pete asks if I want to go back but I feel it would be better to press on as the airplane is carrying over 7000 lbs. of ordnance and I'm not eager to be maneuvering near the ground. Furthermore, I know that dawn is only a couple of hours away and it will be easier to judge my situation in the daylight. We continue on to the target and as time goes by the water seems to be drying up. The altimeter and VVI are beginning to function normally. Pete drops his ordnance and climbs above me so I can drop mine. That accomplished, we head for home and daylight. Still not having complete confidence in the pitot / static system, I ask Pete to take me home on his wing. I join up and fly in formation with his airplane. He flies an approach to landing with me 10 feet off his right wing. When it comes time to reduce power and land, Pete says "You're on your own." and begins a "go-around" and I land.

They call us the "silent" generation. In many ways that is a fair label. We are the guys and women who grew up loving America, during the righteous and patriotic days of World War II. We were too young to go, but old enough to understand duty, honor, and country, and to idolize every hero we heard about from that great conflict. We later had our "draft dodgers", as the Viet Nam conflict had its flag-burners, but the vast majority of us were intensely proud of contributing to the eventual downfall of the evil of the worldwide communist conspiracy.

Typically, we have been silent in the Skyraider Association. Due to the primary purpose of the organization, to commemorate the airplane and the Air Force pilots who flew it so magnificently and heroically in SE Asia, there is, so far, somewhat of a gap in the airplane's history from the end of WW II, when it escaped from Ed Heinemann's Skunk Works, until it went to work with the Air Force in the mid-sixties. During that period, the Able Dog, as we called it, was all Navy. I have been generously welcomed into a lifetime membership in your organization, along with a few others of America's minority flying armed service, based on my tour flying AD's for the Navy right smack in the middle of the cold war. I propose to offer a few paragraphs which will give you a feel for the mindsets of those who fought the cold war, as well as documenting that we felt the same way as you about the AD, when we were flying it from aircraft carriers. This will require my delving into and the reader's tolerating some personal stuff, but I hope it will turn out light and amusing, and not maudlin.

|

I graduated from high school at Kilgore, Texas, in 1950, just in time for the opening act of that "Police Action" in Korea - covered very well in the "Images" section by Commander Burke, an early CO of my fleet squadron (VC 35, later renamed VA(AW) 35-which means, in Navy jargon, "Heavier than air attack squadron, all-weather, 35"). To get back to 1950: after a year of Junior College, I transferred to the University of Texas at Austin, joining the Navy ROTC in the process. I had long before concluded that I wanted to serve a period in the armed forces, and I elected the Navy due to a history of family naval service. My father had sought a Naval Academy appointment for me, to no avail, for a couple of years. There existed a program in those days in which each of the (then) 50 colleges with NROTC would annually nominate two midshipmen to take a competitive test. Of these 100 candidates, the top two scorers were awarded appointments to Annapolis. I participated in my first year in NROTC, and to my amazement I won one of them. After much agony, I turned it down and continued the ROTC route to a commission. Who knows-had I gone to the academy, I might have been right there with you in SE Asia.

The spring of my senior year, we filled out duty preference cards prior to commissioning. I asked for "Small combatant ships, Atlantic". I had only a mild interest in flying of any kind. Then one night my own "Sweetheart of Sigma Chi" (now my wife of 42 years) and I went to see "The Bridges at Toko Ri". I decided on the spot, "I've got to do that!" The next day I applied and was soon accepted for flight training. That fall, I received my degree in mechanical engineering, my commission as an Ensign, and Jodie and I were married. We honeymooned in New Orleans, on our way to Pensacola, Florida, scene of all Navy primary training.

Navy flight training was a highlight of my life (though I confess I was so pleased to be on my own and the husband of Johanna Johnson, formerly of Tyler, Texas, that I might have been euphoric about sacking groceries.) I soloed the SNJ, flew the T-28C, and went to AD's in Corpus Christi for advanced training. The SNJ was great fun, and I carrier qualified in old # 123 (as in "as easy as") with a much coveted "6 for 6 roger passes", meaning I made six carrier landings with no corrective signals from visual acquisition to cut from the LSO. This was accomplished by about one of every 15 or 20 pilots. This was on the "Saipan" and all on paddles.

I was coached at Pensacola to never trust the Air Force, by a Navy pilot who had challenged an F-86 squadron at nearby Egland AFB to an encounter at 30,000 feet with the Navy's new Cougar, F9F-8. According to this officer, "Those cheating Air Force guys showed up at 35,000. If we hadn't been at 40,000, they would have waxed us!"

I remember the T-28C, with its 1,400 h.p. engine, as a delight to fly. I could manage three turns of a victory roll. We were constantly trying to one-up each other, and I developed a trick of raising the gear handle prior to the take-off roll. As soon as the strut lifted off the micro-switches, the gear would retract. That big old engine and a modicum of pilot alertness saw to it that the prop didn't bite any asphalt, and according to onlookers, it was really cool to see the plane seem to come off the runway clean!

Meanwhile, my wife and I made many friends and loved the military life. Among those friends were three special guys and two special gals: Pat and Joye Gray, Dick and Dinah Walls, and Navcad Dave Humphrey. I have pictures of beach outings, and other escapades with this crew. Pat was a big, lovable Texan, Dick a perfectionist Californian, and Dave a fraternity brother and former motorcycle-riding buddy from the University of Texas. More about them later.

On to Corpus Christi, where we added Navy Wings, partial mastery of the Able Dog, and Paula Johanna Nelson to our accomplishments. At Corpus Chisti, one's fate was sealed to the extent of the fleet aircraft to which one would be assigned initially. We almost all wanted jets. To my dismay, everyone was being assigned to S2F's, the two-engined Navy anti-submarine plane. This was regarded as the next worst thing to getting blimps, of which the Navy still had a few. One could extend his service obligation for a year and get jet training-but we learned that the guys who did this were being assigned odd jobs and limited to four hours per month flying, at least for a year or two after earning their wings. Dick Walls had never wanted jets or S2F's. A seasoned lieutenant with fleet experience, Dick had endlessly touted the capabilities and fun of AD flying. Faced with the "stufes", or blimps, when my turn came for an interview with the assignment officer, I crossed my fingers behind my back and pleaded for a jet or AD route (the only routes at "Mainside", the "Stufes being all at outlying fields) based on a need of my wife to reside in Corpus near the Navy hospital, due to a precarious pregnancy (her pregnancy was quite normal.) It worked. Thus did Jodie do me about her 10,000th. good deed, and Paula her first of many--with neither even knowing about it. I never regretted going into AD's. Dick, Pat, and I all went this way. Navcad Humphrey deserted the gang of four by opting for a marine commission.

The AD was designed to outhaul a B-17 on the way in and fight its way out. By the time I met the plane, it had already set a world record for a load lifted by a single-engine plane and had a solid record of reliably delivering the goods, as in the Korean conflict, when it was loaded with wild assortments of rockets, bombs, napalm, etc., which gave the troops on the ground a custom- tailored capability for strikes in support of them. I will never forget my first AD takeoff roll: when I poured the coal to that R-3350, I thought something had exploded! I was hardly over that concern when I saw we were heading about 45% off the left side of the runway. A ton or two of right rudder corrected things, and we were off! We used to say "Feed in about six feet of manifold pressure and three feet of right rudder."

|

We all came to love the AD and gradually concluded that we were the lucky ones. The guys who went the jet route spent their time being vectored from the ground up, whereas we found the time-and the freedom---for flying under bridges, jumping the occasional F-51 "Mustang" we encountered, and generally acting out our individual versions of the "Right Stuff". When one of our number would be killed during training, we would sign his name to the bar chits as we toasted him that afternoon, knowing that out of compassion for his next of kin, the chits would be tossed. Our attitude, or one we attempted, was, "He was a great guy, but he couldn't fly." As to the Able Dog's suitability as a dive bomber: I still have one knee-pad score card from a session which records the following consecutive hits: 40', Bull, Bull, 25', and 40'. (I can't remember how many poorer score-cards I threw away.) I was in a dive bombing pattern when we were advised Soviet tanks had rolled into Hungary. We were ready to go put a stop to all that!

At last came the day I got my Wings of Gold. December 7, 1956---squadron mates were to call this the second worst December 7 in the history of the Navy! Corpus Christi, like Pensacola, had been a ball. The only disappointment came in the fact that my proficiency on instruments resulted in an assignment to VA (AW)-35, an all-weather and night attack squadron flying the AD-5N, the model with a crew of three. I had wanted the one-man version.

The fleet was even more fun than training! Long-range, low-level special weapons delivery and close air support were our main missions. I have flown from San Diego to Washington and Oregon and back with the most prolonged excursion from ground effect being the climbs to pop over telephone and electrical wires. We carrier qualified on the "Kearsage". Finally came the time to deploy to WESTPAC aboard CVA-14, the "Ticonderoga".

After a bitter-sweet farewell to Jodie on the docks at Alameda, CA (following a memorable few days in San Francisco) I settled into my stateroom with fellow Texan and good friend Ed Greathouse, who later would lead the flight in Nam when the four AD's shot down a Mig. An ex-enlisted man, Ed was mature and conservative, whereas I believed we had a duty to be both competent and colorful. I also endorsed the Navy pilot credo of "Better to die than to look bad." I saw this not as grandstanding, but as a way of instilling the pride and confidence which would help ordinary mortals rise to a demand for immortal deeds.

When I began preflight in September,1955, the classes were told: "Look at the man on either side of you. One of the three of you will not make it out of Naval Aviation alive." Such were the odds (in peacetime) in those days. I felt a wave of concern for the two fellows next to me, since each had only a 50% chance to survive! My eight months on the "Ticonderoga" bore out the preflight warning. We lost eight pilots plus some crewmen-an attrition rate of about 15% per year.

|

I do not know whether they found a way to beef up the glorious R-3350 before the Air Force inherited them, but squeezing 2,900 h.p. out of them in the '50's required constant care and a tender touch. I experienced one night ditching at sea, after engine failure. I survived, though I landed in the water without seatbelt or shoulder harness, which I had removed in preparation to jump - only to give that up and hold a panicky crewman in the plane after we were too low to jump. I did this on the guages and flying with my left hand. I hopped out, amazed to still be alive, only to observe my crewman struggling to get free of the sinking plane. I abandoned my life raft, swam to him and helped him get untangled. A destroyer found us and picked us up. I had four more in-flight engine failures (flying as the squadron power-plants officer and thus inheriting the testing of newly overhauled engines and undiagnosed problems). To round out the record, I also survived a carrier deck crash, a hit from an errant (fortunately inert) rocket, a cockpit electrical fire, and later, an engine fire in an S2F.

In between these episodes, we flew around the Pacific, and at an A-1 reunion sometime, I will trade some of these stories for yours of actually fighting with the A-1:

* The night I was vectored in to land on a Cruiser

* Losing an engine for a few seconds during a night cat shot-with an Air Force Lieutenant General as a passenger.

* Rolling an AD with 6,000 lbs of bombs under the wings.

* The day Dick Walls and I gave tight formation flying a new dimension by flying briefly with our wings touching.

* The day at Cubi Point when I discovered a lot of brass in their whites waiting with a cake to cut in celebration of the one millionth landing at the field, ran to my plane, took off, bent it around and dove in-only to be aced out by a chopper and nearly courtmartialed. Fortunately a Captain with a sense of humor said, "Son, I've got to either court marshal you or commend your aggressiveness and initiative. I don't want to put a damper on this party, so come on in and get the second piece of cake."

* The day I almost got to fly Jane Mansfield aboard the ship.

* Rolling an AD below sea level.

* Some truly important and professional flying in addition to all the above.

At last the ship turned east. I had loved every minute of the Navy, flying, and especially the Able Dog. But I decided not to put my family in the position of living with me gone and the one out of three odds. In late May of 1958, I wrote Jodie, " I want nothing more than to never again leave you and our children. But I confess I will miss hearing the speakers roar out, "Pilots, man your planes." And "Pilots, start your engines." After almost 40 years, I still miss it.

I rounded out my tour in the home squadron (ending with about 1,000 Spad hours and 104 carrier landings, 37 of them at night) and entered civilian life in late 1958. I flew in the Reserves for a few years and then hung it up. I continued flying, instructing in primary, basic, commercial, instruments and aerobatics. I owned, or owned shares in, a couple of Piper Archers, a Piper Dakota, and a Grumman Tiger. Jodie and I and our three daughters have flown many enchanted hours together, until August of 1996, when worsening of my Parkinsons Syndrome, plus, including this year, four episodes of heart surgery, rendered a new medical impossible. I, of course, miss flying. Still, having experienced all I did, in my total of 3,500 hours flight time, I would be an ingrate to complain. Life was - and still is-good to me.

|

Now back to the gang of four from Pensacola: Dick Walls, Pat Gray, Dave Humphrey, and me: I am the only survivor, the others having given their lives to duty, honor, and freedom within five years of our pinning on the Navy wings. Dick augered into the target one night during dive bombing practice. Pat failed to survive a low ejection from a flamed-out FJ "Fury"(the Navy F-86), and Dave bought it due to never explained circumstances while flying a Marine F4D "Skyray". I couldn't attend the funeral of any except Pat Gray, whose four year old son I held, while "Taps" was played and a volley fired honoring his father. None of us had the privilege of flying combat for our country. My hat is off to those of you who Flew and Fought. Yet I would be untrue to my old friends if I did not ask you to honor the patriotic unsung heroes of the silent generation who laid all they had on the altars of duty and freedom in the time between wars, when constant readiness to fight if we must illustrated to the communists the futility of their hopes of world domination.

My Navy days scrapbook is dedicated as follows:

To all who served their country in the cold war and survived is offered the words attributed by Shakespeare to Henry V of England in addressing his troops on the eve of the battle of Agincourt, their stunning victory over the French in 1415:

"He that outlives these days and comes safe home will stand a tip-toe when these days are named....He that sees old age will strip his sleeve and show his scars....This story shall the good man teach his son....and the gentlemen who were then abed shall think themselves accursed that they were not here, and hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speak that served with us."

To those who, like Pat Gray, Dick Walls, and Dave Humphrey gave all to defend freedom, is promised:

Lengthening shadows of time, and the gentle haze of history being forgotten and transgressions forgiven, dim memories of the cowardly and the self-serving, whose share of the burden you helped carry. But memories of you will be forever sparkling, crisp, and new. They are eternally enshrined in the hearts of those still alive who knew you, and who, like you, laid all they had on the altars of duty and freedom......

I am struck with how similar in sentiment my dedication is to the feelings and motivation of the Skyraider Association. Surely your faith in your country and American principles, without diminishing the pride I have in the silent cold war my generation fought, called for far more sacrifice. Therefore, I am proud to join you-and I hope you will welcome all other cold war Navy Spad drivers as comrades in a high cause, as well as lovers of the best airplane that ever flew. Duty. Honor. Country. Freedom. We fought-or stayed ready to fight-for the greatest country in the world, and for each other.

Tom Nelson-"Tiger One"-reporting for duty, sirs! December 31. 1997

I will leave this one to your judgment. It is a bit long, but reflects some of the odd jobs the Navy guys did in the Spad. At the time the tow mission was a pain and the planes were not kept up, but it did make for some real variety. Do with it what you like. Maybe it will get us out of the valley we are in at present. ..Reid

From 1959 until 1962 I was a member of Attack Squadron 85, flying the AD-6. On each of my three cruises, when our Carrier, the Forrestal, arrived in the Mediterranean, we were assigned one additional plane by SIXTH FLEET. It was the AD-5 (aka A1E, Tow plane, Skyraider). This aircraft has two adjacent seats in the front cockpit, and a large area in the back that had been used by the Navy for medical stretchers, ASW equipment and operators, or AEW equipment and operators. The SIXTH FLEET version had the rear area rigged for airborne target towing with an operator, reel and cable. The purpose was for the Tow Planes to provide an airborne towed rectangular targets for the small ships, destroyers and cruisers, to shoot at. The AD-6 and the AD-5 were very different aircraft in the way they handled this task.

In 1960, several weeks after Forrestal arrived in the Med, VA-85 was advised to pick up a Tow Plane, as we departed Naples, Italy. The Skipper had assigned himself the job of going to the Naval Air Facility in Naples and flying the plane out to the ship after Forrestal departed the harbor. He and I were spending the evening at the NATO Club, Bagnoli, when he met an old friend. He ordered me to get the plane to the ship the next morning. I gladly took the assignment, without a thought about having never flown or seen the inside of the AD-5.

At the Naval Air Facility, the next morning, there were four Tow Planes to choose from. One had a wheel removed and another did not have an engine. The flight line could not find the log book of one of the planes so I chose the aircraft with wheels, log books and an engine. The log books left much to be desired, having not been kept up. I would learn later that it was impossible to determine what maintenance had ever been done nor could anyone tell from the records the type of engine ignition system. These planes were passed from ship to ship in this way, and no one asked questions. This was the beginning of my three cruise adventure.

Shaky start...

I pre-flighted the Tow Plane,

still somewhat worn out from the night before. A young Second

Class Ordnanceman climbed in the right seat and let me know that

he was the tow reel operator. I sat in the cockpit for five minutes,

trying not to give away my problem. He finally leaned over and

pointed to the battery switch so that I could start the engine.

Once the engine was going, I began a slow taxi toward the runway,

trying to locate and turn on the radios. I was used to aircraft

with one radio and one off/on switch. This plane had three types

of radios with master switches, toggle switches and other switches

which were installed

wherever there was an open space. By the time I reached the runway,

with the help of the young Operator, I had managed to turn on

the radios so that the tower could talk to me. I took off, thought

about a practice touch and go landing, but decided not to push

my luck and headed for the ship.

The Forrestal was just clearing Naples Harbor. Rather than letting me land, I was instructed to fly over to a group of Destroyers so that they could practice their anti-aircraft gunnery. Say What?? The Operator again told me what to do, including airspeed and altitude. He had saved me from a red face again. Once the tow mission was completed, I arrived back over Forrestal. The Air Boss instructed me to make a "Down-wind" recovery, landing a plane aboard the ship with the wind instead of against the wind the normal way. Say What?? I had never done one and I was not too excited about complicating my first landing in that Tow Plane. I think my next transmission was," Due to amount of time of pilot in type, I recommend that you turn into the wind.", but I did not say,"NO". The furious Air Boss called my Skipper, still asleep in his stateroom. "Your Pilot refused to take a downwind recovery , what is his problem?" My Skipper suddenly awoke with, "My God, it is Reid. He has never flown that plane before". Below I could see the ship making the unwanted turn into the wind, to bring me aboard.

I made an uneventful recovery. As I taxied forward I turned to my crewman and said, "I have never flown this kind of aircraft before." The shaken Operator said, " I know, I know!!" Two weeks later, after flying with several other pilots, he listed me as one of the three pilots he trusted and felt safe enough to fly with. I never asked why. I was chewed out for refusing to take a downwind recovery, but not with much enthusiasm. The Squadron was ordered to "field qualify" all tow plane pilots and to schedule some practice carrier landings. I was told that I was already qualified and assigned several flights in the right seat as an observer. This was the beginning of an interesting relationship.

The Tow Plane was used for more than towing. Most of the time we spent running people all over the Med. In the three years I flew this plane I went to Palma, Valencia, Barcelona, Zaragoza (in Spain); Naples, Pisa, Palermo (in Italy); Athens, Greece; Nice, France; and Malta. The opportunities for good "liberty" were endless. We would fly the Shore Patrol into a port two days before the ship arrived. Quite often we would remain in port until the ship was back at sea.

Some minor 'Snags'...

I do not have much recollection of problems during my second cruise, that is, I had the same number of take-offs as landings. I enjoyed giving the small ships towing services. The crews appreciated our work and we had fun working with them. We tried to do different tow profiles to relieve the monotony. I tried a dive run on one ship, but the cable broke and the target and a good part of the broken cable draped over the mast of the ship. On another instance the SIXTH FLEET Flagship came over the horizon and ordered me to detach from the Destroyers and begin to service the Cruiser. The controller on the Cruiser started giving me orders and being most critical. He said I was too high or too wide or not on airspeed. Finally, I got fed up and said I would only take up assigned headings as he instructed, and pretty soon I was nowhere near the Ship's gun range, out in "left field". He then asked nicely if I would simply fly up the side of the ship and I did as he asked. He gave the standard "This will be a live firing to starboard", just as a voice from one of the Destroyers announced that," the water temperature is 68 degrees", implying that I might be shot down by the Cruisers guns. The controller was furious and put us all on report. The Admiral's staff back on Forrestal would have made me feel more threatened if they had kept a straight face while chewing me out. No sense of humor on the Flagship, I suppose.

One takeoff, one (water) landing...

On the third cruise, it got

interesting. On one occasion, two of our Air Wing pilots had gone

through a NATO Survival and Evasion school in Turkey. After two

weeks of evading, they rowed a raft to catch a submarine which

took them to the island of Rhodes. From there they were flown

to Naples, Italy, where they were when I dropped off two shore

patrol officers from Forrestal. They asked for a ride back to

the Carrier and I agreed, even though neither had any proper flight

gear. When we arrived over Forrestal, I was instructed to remain

airborne for an additional hour and a half. To reduce the boredom,

I wandered around and found a solo AD-6 off another Carrier, the

Franklin Roosevelt. I made a run on him, pulling up in front of

him with a roll. He called me on UHF Guard to say that I was on

fire. A look at my gauges gave no indication of fire, but the

zero oil pressure was an attention getter. I called "Mayday"

and headed for the Carrier. I had to take a wide long final for

landing because the flight deck was still had not been cleared

of aircraft. At about a quarter mile, with my landing gear still

up, I tried to add some power just to be sure it was available,

before dropping my gear. The prop froze. The pilot riding in the

right seat, John Clinton, was an experienced AD-6 pilot, so he

had full knowledge of our condition. The pilot riding in the back

had only jet experience, and was clueless that we were going to

crash. John tried to yell a warning back to him, but gave up.

We decided he would catch on very quickly when

the water began to rise. We had a nice smooth water landing (ditch)

right under the helicopter, who was already lowering the hoist.

As I unstrapped, I was happy to note that the jet pilot had indeed

caught on and beat me out of the sinking aircraft. I walked out

on the wing, jumped into the water and caught the helicopter's

recovery collar after

just two strokes.

The accident board was conducted, not without some humor. There was one statement that I "took off from Naples and flew out to the ship, almost". The Skipper was critical of me for flying passengers without flight gear, but I think he would have offered them a ride, as I did. I was approaching the end of four years in the Squadron; they had some fun with me. My punishment was that I had to go to Naples and get another Tow Plane. This time the selection was even worse than three years earlier, since our Squadron had ditched the two "good ones". Twice a day I flew the same clunker, landed and documented a long list of maintenance problems. I was broke, and now married, so I was more than ready to get back to the ship. After a week I gave up and headed the replacement tow plane out to the ship, sounding like a model "T", complete with smoke and backfires. I honestly thought that the ship's mechanics could fix this mess, where the Naples crews could not. I was wrong.

To the Aircraft Graveyard...

The replacement aircraft never

flew from Forrestal for the rest of the time in the Mediterrainean.

The Flight Deck Crew had a cake for the 100th time they towed

the plane back to the island, when it failed to takeoff. It was

ordered to be stricken and taken to an aircraft graveyard in Arizona,

upon return to the States. As we approached the coastline of the

States, I was assigned that hunk of junk for the fly off, with

two passengers. When I turned up the engine, you've never seen

so such smoke. Since I was officially qualified at ditching, I

saluted the Catapult Officer, the signal to launch me, but he

could not see the

salute in all the smoke. Bud Roemish, sitting in the right seat,

un-strapped, stood up and saluted before dropping back into the

seat to strap back in. The Catapult Officer shrugged and sent

us off. It took some work, but I got that plane to 2000 feet and

headed in to N.A.S.

Oceana and one last emergency landing. My last Spad flight.

At the end of the cruise, I was transferred to N.A.S. Meridian, Mississippi. About nine months later this same aircraft landed on its way to the desert grave yard. The Ferry Squadron pilot gave up and left it there. There was a local request for any qualified AD pilot to take it to Pensacola. No way!! But of late, I have begun to wonder if the Navy gave Buno 132444 to the Air Force.

Here is a very short story I sent back to another fast mover driver when he asked if I flew A-1s. It might be suitable for your A-1 stories

I was in the 602nd Ftr Sq (66-67) flying A-1Es as Sandys and Fireflies. I was Sandy 1 the day Leo Thorsness got shot down (4/30/67), and despite the B.S. put out by Col B*#*. (Thud Ridge author) we got to the scene from our orbit point as fast as our Spads would take us. I have talked to Leo since his return, and he tells me he was already in enemy hands when we flew over the first time. While my wingman and I were searching Leo's area there was a real MIG call, just ask Joe Abbott Jr. As prebriefed, I jettisoned external fuel and everything else except rocket pods. I figured on the deck I could turn into any fast mover, and a facefull of rockets might just save my ass. It was my "last ditch" plan. It turned out later that I would miss the avgas I left up north. My wingman didn't jettison when I told him to, so he ended up back at Udorn that night, but I get ahead of myself in this story.

I don't remember how long we stayed in Leo's area, but after a thorough search with no contacts, I told Crown we would RTB. On the way south we heard about Joe Abbotts successful bail out (a MIG got him), I can't remember his call sign that day, but we took vectors to his last known position. We found him in some hills just north of the Black River, had voice contact, and confirmed his location. We passed this to Crown and requested the Jolly Greens to cross the border inbound. After some radio delay we were told one of the Jollys had developed a hydraulic problem and they could not proceed. I got the dubious honor of passing the news to Joe and assuring him someone would be back at first light the next day. He has since told me he was captured that evening. I have a mental picture of the valley where we found him burned into my permanent memory and I could point out the trees where we left him, to this day.

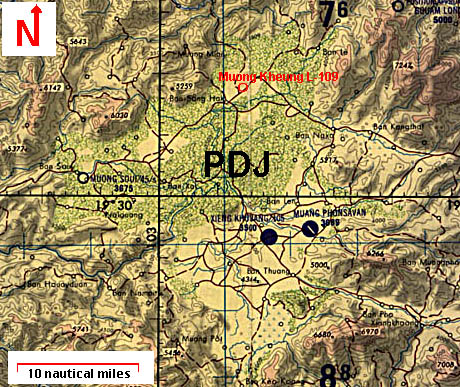

By this time I was Bingo minus a bunch for

RTB, so I took up a heading to L-109, a 5200 foot long dirt strip

on the N edge of the PDJ that we had been told was still in friendly

hands. It was high overcast, twilight, and hazy when my wingman

told me he had lost sight of me. I gave him a heading and pressed

on. I still didn't know he had enough gas to get home. The next

radio call I remember was my wingman telling the world he was

on fire. I gave him the standard dash-1 advice "Bail Out"!

I made a hard left turn to look behind me since that is where

I assumed he was (left, because that was the side we sat on in

our two seaters so the quickest way to check 6). I saw a fireball

appear on a hill a couple miles behind me, and a few minutes later

my wing man came on the air and said he had blown the fire out

in a steep dive. My guess is the fireball I saw was a spent SAM.

I then learned he had enough gas to go home and told him to just

go south. I may have even turned off squadron common at that time.

I still had about a 20 minute cruise to Lima-109. Fortunately, once I was in Laos, Crown came with me AND had flares on board. When we got to the dirt strip it was pitch dark on the ground. I asked Crown for some flares and made my first pass. Their wasn't enough light to line up and put it on the ground. By then, I knew if the fuel gage was right I could only make one more attempt. Now since this is my story, and there are so few wittnesses, and I don't know if the tape still exists, as I recall I calmly pulled up into a closed pattern and asked Crown to drop every damn flare they had on board, they complied and I executed a greased 3 pointer in the first 100 feet of the dirt runway. Turned out their were two U.S. Army types living there and they informed me there had been a "short round" incident involving some A-1s the previous week and they didn't think a native feast was in order that night. I shared a little of their food and after a restless night, was up at first light and we gassed up my Spad, over the wing from 55gal. drums.

It was a clear morning and we watched as the Alpha strike went north to try to find Joe Abbott. Later that day I returned to Udorn. As they say the rest is history. The mission on the afternoon of April 30, 1967 lasted 5.1hrs. according to my Form 5 and I'll never forget it. The only good thing that happened that day was I walked away from another landing. Yes, I flew A-1s.

-CK 6 Bob Russell